The Marine Environmental Awareness: Knowledge, Media, and the Politics of a Thriving Underwater World (1870–1980)

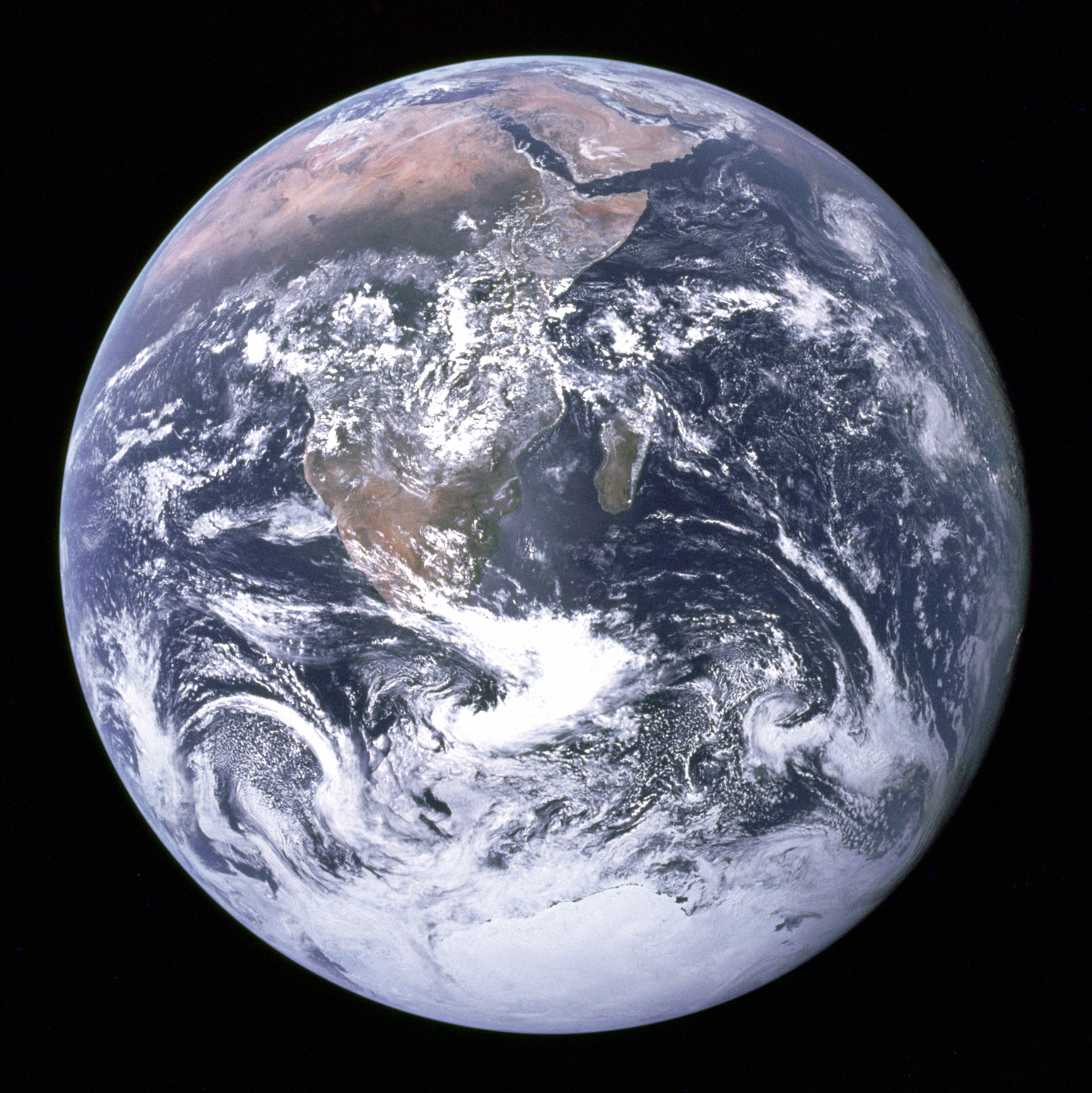

The image of the “Blue Marble” became a symbol of environmental protection and of a new planetary consciousness during the second half of the twentieth century. While it was the oceans’ water that rendered this image blue, current environmental history still considers the emergence of an environmental awareness in a land-based way. The common road into the ecological era leads us through events on solid ground. The appearance of Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring (1962), the oil crises (1973 and 1979/1980), as well as the formation of the environmental movement in civil-society, counted as the indicators of a new awareness of nature’s needs.

In contrast to this narrative, this project develops the thesis that the marine biological research of the German Empire created the fundamentals of our current environmental awareness. These fundamentals include the concepts of “biocenosis,” “ecology,” and the “environment.” The project’s guiding question is how this specific knowledge of marine animals evolved into the broader understanding of the environment on a global scale. This issue is addressed through three themes.

The first theme is the institutionalization of marine biology as a field of knowing and way of understanding the marine world between the 1870s and 1930s. The second core topic focuses on the emergence of film technologies between the 1920s and 1960s, their ways of making the underwater world visible as ecological systems and connecting marine animals to human culture. The third theme concentrates on development politics as a heuristic laboratory. This theme demonstrates the shift that took place between the 1960s and 1980s and changed the ocean’s meaning from a utopian resource reservoir to an asset deserving protection.

The project transcends the boundaries of its more limited topic through three aspects. Firstly, the traveling marine biologists, network of global research stations, and the resulting media, economic, and political connections put processes of globalization during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries on the agenda. This longue durée perspective completes the hitherto existing emphasis of German global history on the times of the Empire. Secondly, marine biology as a form of knowing marine life brings animals as part of the environment to the fore, whereas the human relationship with nature has occupied environmental history up until the current day. Thirdly, it has to be considered whether the ocean as a fluid historical space and emerging new field of knowledge offers innovative methodological potential for environmental history, the history of science, and modern history in general.